“104. No precautions were taken. Tip 7 was started at Easter 1958, because (as we have already said, paragraph 28) the farmer’s complaints rendered impossible any further use of Tip 6. There had been a certain amount of tipping previously between Tip 3 and Tip 4 but this was insignificant. Three people went onto the mountainside to consider a new tipping site. Of these, Mr. Vivian Thomas played so subordinate a role in this matter that he must be absolved from the responsibility for the decision then made. The other two, Mr. Joseph Baker (No. 4 Group Mechanical Engineer), and Mr. R. N. Lewis (Merthyr Vale Colliery Manager) were jointly and severally quite unfitted by training to come to an unaided decision as to the suitability of the proposed site. To recapitulate: they had no Ordnance Survey map, and they took no plan with them, because none existed; they made no boreholes; they came to no conclusion regarding the limits of the tipping area; and they consulted no one else — not even the Colliery Surveyor. They arranged for no drainage, for they considered none necessary. It was a case of the blind leading the blind, and, as Mr. Geoffrey Howe, Q.C. rightly added “. . . in a system which had been inherited from the blind”“.

“Findings:

I. Blame for the disaster rests upon the National Coal Board. This blame is shared (though in varying degrees) among the National Coal Board headquarters, the South Western Divisional Board, and certain individuals.

II. There was a total absence of tipping policy and this was the basic cause of the disaster. In this respect, however, the National Coal Board were following in the footsteps of their predecessors. They were not guided either by Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Mines and Quarries or by legislation.

III. There is no legislation dealing with the safety of tips in force in this or any country, except in part of West Germany and in South Africa.

IV. The legal liability of the National Coal Board to pay compensation for the personal injuries (fatal or otherwise) and damage to property is incontestable and uncontested.“

(Quotations from the 1967 Tribunal report inquiring into the disaster at Aberfan on 21 October 1966, Chaired by Sir Herbert Edmund Davies, Court of Appeal judge).

There is no need for the title of this piece to end with a question mark. The point cannot seriously be argued against by anybody, such was the total absence of any stability of waste tips system above Pantglas in Aberfan.

The central theme of this blog, in relation to Welsh rugby, is the need for good structures and systems. But these are sound principles of universal application across business and sport and many other walks of life. Even the best individuals make mistakes, hence the need for systemic safeguards with checks and balances. Remember how the 1762 founded UK merchant bank, Barings, collapsed in 1995 over the actions of one unsupervised derivatives trader in Singapore who generated hidden losses of £827 million?

I looked earlier this year at the Hillsborough disaster (link). A policing of capacity crowd FA Cup semi-final matches that had very little safety margin for error to begin with and resulted in a disaster when the “human safeguard” of Ch Supt Brian Mole was suddenly removed from the equation/”system” and he was replaced following the Ranmoor prank by the novice Ch Supt David Duckenfield. A dangerous situation was allowed to develop outside the stadium and then catastrophically imported inside the narrow and far more dangerous confines of the stadium without the requisite follow-up action i.e. the need to close off access to the central tunnel to the already crowded Pens 3 & 4 before opening any exit gates to relieve the serious crushing that had developed outside the stadium. New entrants needed to be directed to the half-empty wing pens and 96 soccer fans died when this did not happen.

This Friday, the 21st again being the last Friday before school half-term as in 1966, will be the 50th anniversary of one of the grimmest days in Welsh history. 21 October 1966. The worst disaster involving children in modern UK history.

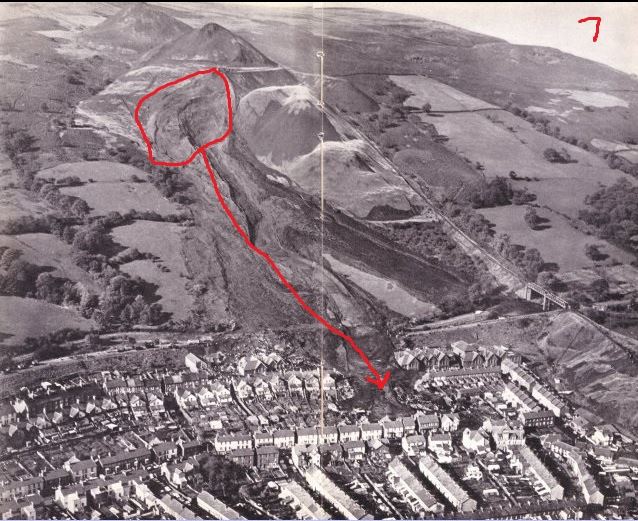

The catastrophic slide down the eastern side of the sandstone Merthyr mountain in the Taff valley of the active No. 7 tip, liquefied by springs underneath it, within the Aberfan waste tip complex of the Merthyr Vale colliery in the No.4 (Merthyr) Group of 5 collieries within No.4 (Aberdare) Area in South Wales of the South-Western Division of the National Coal Board (“NCB”).

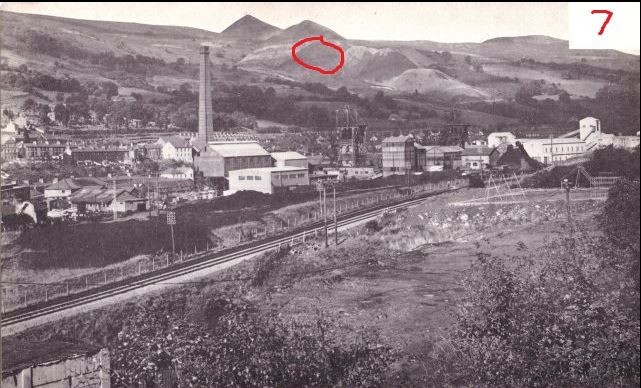

This massive breakaway from No. 7 waste tip (I have circled above, below Tips 4 & 5 higher up the mountainside, in this photograph taken before the disaster), the only active tip and commenced at Easter 1958 and estimated by October 1966 to be about 111 ft high and to contain about 297,000 cubic yds of colliery waste, the liquefied slurry overwhelming in its downwards course two farm cottages on the mountainside and killed their occupants.

It then crossed the disused Glamorgan Canal, severing the water mains from Merthyr to Cardiff to add to the slurry chaos, and surmounted the embankment of a disused railway line. It then engulfed and destroyed a (junior) school and eighteen houses and damaged another (secondary) school and other dwellings in the village before its onward flow substantially ceased and solidified. It killed 144 people, 116 of them children and mostly aged between 7 and 10 years of age.

There is a perception that the Aberfan inquiry was a whitewash, because of the aftermath of nobody losing their jobs. Especially the autocratic stonewalling NCB Chairman, Lord Robens, whose contradictory testimony the NCB’s own QC asked the inquiry to ignore. The NCB realising that they could and should have prevented the disaster before the inquiry began, but audaciously not admitting this until closing speeches on the 74th day of the inquiry. Appalling insensitivity by a state-owned industrial monolith towards a small community whose livelihood depended upon it, even raiding the disaster relief fund to help pay for the removal of the waste tip complex. A financial wrong not partially remedied until 1997 and not fully remedied until 2007.

Nothing could be further from the truth about the actual Aberfan inquiry, whose job it was to investigate causation. It had no punishment powers. It ruthlessly analysed and took apart one by one the systemic failings that led to the disaster. The survival of Lord Robens was more to do with the values and politics of a very different era.

He was a powerful former Labour Party politician and trade unionist, well connected and popular in the mining industry for his strong opposition to the emerging nuclear power industry, undertaking for Harold Wilson a massive pit closure programme that dwarfed the later Margaret Thatcher final run down of the industry and all being done by Lord Robens without a big confrontation with the then powerful NUM. Annually 7-10 NCB collieries were being closed in South Wales in the mid-1960s, but with pre-existing manpower drift and accompanied by investment in the remaining designated long life collieries and with jobs at that time outside of the industry unlike later in the high unemployment 1980s/early 1990s.

The report, if you read it, and I highly recommend that you do, is absolutely scathing of the NCB at almost all levels (HQ in London, the South-Western Division covering South Wales and the local No.4 (Aberdare) Area that included the No.4 (Merthyr) Group of 5 collieries including the Merthyr Vale colliery itself at Aberfan).

The Chairman of the Tribunal, Sir Herbert Edmund Davies, was a Court of Appeal judge from 1966-74 and then a Law Lord from 1974-81. If you want a tenuous rugby connection in this piece, deputy counsel to the Attorney-General at the inquiry was Tasker Watkins QC. Earlier a recipient of the Victoria Cross in the Battle of Normandy in 1944, later a Court of Appeal judge (including as the deputy Lord Chief Justice from 1988 until his retirement) between 1980-93 and finally (in his dotage) President of the Welsh Rugby Union between 1993-2004. One hell of a CV. Representing the local residents of Aberfan? Desmond Ackner QC, a renowned cross-examiner with no connection to the NCB/South Wales, another future Law Lord (1986-92). Analytical legal brains of the very highest quality.

Lord Edmund-Davies of Mountain Ash Grammar School and Sir Tasker Watkins VC of Pontypridd Boys Grammar School, in the days before widespread dumbing down and when rigorous analysis were still highly valued in Wales. Two excellent judges in a recent tradition of senior Welsh judges, from Lord Morris of Borth-y-Gest (Law Lord, 1960-75) to the current Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales, Lord Thomas of Cwmgiedd. And Geoffrey Howe QC, later Chancellor of the Exchequer and Foreign Secretary, representing the colliery managers association.

The South Wales mining industry was no stranger to tragedy, especially given the high quantity of firedamp in many of the coal seams and especially in the fiery dusty dry steam coal collieries of certain East Glamorgan valleys.

439 miners killed at the Universal colliery explosion in Senghenydd on 14 October 1913, the largest ever coal mining loss of life in the UK. Poor practices at the colliery, some amounting to legislative breaches even in that era, and simply ridiculous at a well-known fiery dry steam coal colliery that had already suffered a previous serious explosion in 1901.

A non-reversible ventilation fan system, main haulage roadways where the sides/roofs were not being cleaned of coal dust, trams open at each end but for a bar, no breathing apparatus stored at the colliery, ventilation so poor that even some working districts and main underground haulage roads were wholly or partially in the return airway to the upcast shaft from other working districts.

Amongst the other disasters, 290 killed in the Albion colliery explosion in Cilfynydd just north of Pontypridd on 23 June 1894 and a colliery basically just the other side of the mountain from Senghenydd in the Aber valley. Ignited firedamp with coal dust again. But it was another incident at the Albion colliery on 5 December 1939, itself only a few miles south of Aberfan, without loss of life and a lesson that went unheeded, from a colliery that itself was to be closed the very month before the Aberfan disaster, that led to the tragedy in Aberfan on 21 October 1966.

After a period of heavy rainfall, on 5 December 1939 a large slide of a waste tip belonging to the Albion colliery situated on the hillside adjoining the main Cardiff-Merthyr road, slid some 710 feet to the road, crossed it, and then progressed a further 720 feet to beyond the river bed. The width of the slide below the tip was 400 feet, the main road was blocked for 585 feet to a depth of 20-25 feet, the Glamorgan Canal was filled for 540 feet and the railway for 500 feet. The River Taff was blocked to a depth of 15 feet for some 500 feet and substantially diverted. It was estimated that the total weight of the tip material in the slide was some 180,000 tons. But, amazingly given that it had severed the main road and the main railway line between Cardiff and Merthyr, there were no fatalities. A memorandum on the sliding of colliery tips was prepared for the private owners (Powell Duffryn), but it seems to have been filed away and mostly forgotten with the nationalisation of the coal industry in 1947.

But there were also warnings at Aberfan itself. On 27 October 1944, a large portion of Tip 4 slid down the mountainside for a considerable distance, estimated at 1,800 feet and stopping only 5-600 feet before the disused Glamorgan Canal. Yet another slide at the disaster Tip 7 in November 1963, after which flooding down in Aberfan became more pronounced as the mountain’s natural drainage was further damaged. But tipping on Tip 7 continued, with no tipping instructions from management beyond no more tailings waste product and with no inspections of stability. Indeed, many managers remained unaware of the 1963 slide. At Group and Area level, not just further up at Division level. Not even a further believed waste tip slide at another colliery in 1965, the Ty Mawr in the Rhondda, raised the alarm in relation to the perilous situation existing above Aberfan.

But what is astonishing, in a manner which engenders real anger, is the total void in relation to where there should have been a system of colliery waste tip stability in place:

(1) Although it sounds crazy, especially in today’s more health & safety conscious world, the NCB did not even have any national or divisional policy in relation to the siting, control, inspection and management of colliery waste tips. The NCB directors in London had never discussed it, and localised pre-nationalisation practices had continued in the absence of any national policy or system regarding spoil safety. Tasker Watkins QC expressed it as ” ..personal responsibility is subordinate to confessed failure to have a policy governing tip stability . . . It is in the realm of an absence of policy that the gravest strictures lie, and it is that absence which must be the root cause of the disaster.“

(2) The legislative framework provided no help at all. Such was the fixation on the inherent dangers of deep underground mining that the inquiry tribunal, despite the obvious dangers involved with waste tipping on the side of steep and wet V-shaped valleys as in the South Wales coalfield, discovered there was no UK legislation on the subject. Indeed, on a global basis, the tribunal could find only legislation on waste tips at the provincial level in Germany’s Ruhr and at the national level in South Africa.

(3) In the absence of statutory provisions imposing responsibility upon them for tip safety, it is perhaps not very surprising that Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Mines and Quarries had given no thought to the subject. Senior inspectors in Cardiff were unaware of the major October 1944 slide at Aberfan until after the October 1966 disaster. There was no need to inform the inspectorate in 1944, inasmuch as no-one working on the tip had been killed or injured. As the Tribunal noted, that position at law remained in October 1966. 144 had been killed, mostly children, but no on duty NCB employees had been killed or injured. As the tribunal caustically put it “Accordingly, the Merthyr Vale Colliery manager was not under any obligation to report even the appalling Aberfan disaster to the Inspectorate.” Madness!

(4) The dangers with mountainside waste tips had been appreciated for 40 years, long before nationalisation. Professor George Knox in 1927 at the South Wales Institute of Engineers in Cardiff delivered a paper entitled “Landslides in South Wales Valleys“. It gave full warning of the menace to waste tip stability presented by the uncontrolled presence of water, and the severe risks if proper drainage was not undertaken. And yet several of the tips at the Aberfan complex were built on underwater springs and surface streams, clearly marked on maps and/or visually obvious. The fatal No.7 tip was even advancing onto the slide run in October 1944 of the No.4 tip, a rather obvious further stability problem itself.

(5) A tradition/practice from private ownership, that was carried over to the NCB upon vesting day and nationalisation in 1947, was that the responsibility for waste tips was traditionally placed on the colliery/unit mechanical engineer and this allocation to colliery mechanical engineers continued up to Group, Area and Division level. If a tip stood it must be stable, was the prevailing mind set. These men were not qualified civil engineers, and industry habits did not change after more civil engineers were employed by the NCB from the mid-1950s. The mechanical engineers were left uninstructed as to the methods of ensuring tip stability and detecting the signs of instability. The No.4 Area mechanical engineer conceded that they all “lacked any real appreciation of the basic elements of tip stability“.

(6) Matters were even more complicated in the No.4 (Aberdare) Area, that included the Merthyr Vale colliery within its No.4 (Merthyr) Group, because there was no appointed chief engineer and the mechanical engineer and the civil engineer were barely on speaking terms let alone collaborating with each other.

So when a report on tip stability was requested from all areas by the Division chief engineer in April 1965 following the Ty Mawr colliery incident in the No.3 (Rhondda) Area (his Division mechanical engineer’s father having been a recipient of the 1939 Powell Duffryn memorandum and having provided him with a copy of the memo), in the No.4 (Aberdare) Area it was sent to both the mechanical engineer and to the civil engineer (but not to the area manager or to the area production manager above them). The civil engineer did nothing, leaving it to the mechanical engineer (the more dominant personality).

And there is doubt whether the former visited the tip complex at all before submitted a wholly inadequate report. He spoke with nobody, if he did, at the colliery or in the tipping gang. All the warning signs were there, but there was nothing in the report that alerted the Division chief engineer to the need for an independent civil engineering report whose commissioning would undoubtedly have averted the subsequent disaster.

(7) Even the actual tipping gangs, including the tipping gang at the Aberfan waste tip complex, had received no training whatsoever on tip stability. None of that gang had apparently ever worked at another colliery waste tip complex.

(8) A Division that was more pre-occupied with pit closures and the inquiry aftermath of the firedamp explosion on 17 May 1965 which killed 31 miners at the Cambrian colliery in the Rhondda Fawr. A death toll that would have been far higher if that colliery was not already being run down for closure with manpower transfers to other long life collieries. Waste tips ultimately the operational ancillary responsibility of the Division’s production director, an individual who upon appointment in the early 1950s was responsible for coal production at 178 collieries and still, even by the time of the disaster, was responsible for production at the remaining 75 collieries within his domain.

(9) Communication within the NCB was remarkably poor. We have seen in the opening quote how the former colliery manager (by the time of the disaster the manager of the No.4 (Merthyr) Group) and the former No.4 (Merthyr) Group mechanical engineer (accompanied up the mountain by the colliery/unit mechanical engineer) came to site the No.7 tip in 1958 without any upwards or external communication. We have also already seen the poor relations and non-communication in the No.4 (Aberdare) Area between the mechanical engineer and the civil engineer.

The Division’s production director (previously manager of the Merthyr Vale colliery, 1940-42) was aware of the December 1939 Cilfynydd and October 1944 Aberfan slides, but testified he was unaware of the November 1963 Aberfan slide. The Division’s chief engineer (a mechanical engineer) testified that he was unaware of the October 1944 Aberfan slide and had no personal knowledge of the details of the December 1939 Cilfynydd slide. When, as part of the report on tip stability requested from all Areas by the Division chief engineer in April 1965 following the apparent slide at the Ty Mawr colliery, and having sent out the 1939 Powell Duffryn memo re-hashed, the Division’s chief engineer did not consult with the Division civil engineer before preparing and sending and did not send a copy of either the re-hashed memo or the request for stability reports to the No.4 (Aberdare) Area general manager and/or production manager above the estranged mechanical and civil engineering pair.

The Division mechanical engineer, despite tip stability concerns going back to his personal attendance at the December 1939 Cilfynydd slide and providing the chief engineer with the 1939 memo he had obtained from his own father, had never consulted with the Division chief civil engineer on the subject of tip stability since his appointment in 1958. When the No.4 (Aberdare) Area mechanical area apparently inspected the tip in 1965, he did not even notify his attendance to the Merthyr Vale colliery manager or to the colliery/unit mechanical engineer responsible for the tip. Neither did he exchange a single word with the actual tipping gang at the site, including the tip charge hand.

The No.4 (Merthyr) Group manager since 1961 of 5 collieries in 1966 (formerly the Merthyr Vale colliery manager from 1951-59, and who had jointly selected the No.7 tip site – see opening quote) testified he was unaware of the November 1963 slide at all.

Utterly utterly dysfunctional, in terms of internal corporate communication.

(10) The final issue, when local concerns were so widespread and the problems were so obvious, including increasing flooding down in the village as the mountain’s natural drainage was being ever damaged by the ever expanding waste tip complex, is why there was no vigorous action taken by the Merthyr Tydfil Borough Council? And by the powerful NUM? There was substantial correspondence between the council engineers and the Merthyr Vale colliery, NCB No.4 (Merthyr) Group and No.4 (Aberdare) Area in the early and mid-1960s, but it was never taken higher up the NCB to Division or National level in the absence of any real progress. The council was successfully fobbed off regarding the waste tip complex. The dangers inherent in having lots of small councils, should any one of them be faced by an economic colossus like the the NCB in the 1960s.

The real answer perhaps rests in the economic circumstances of the day. The 106,000 miners in South Wales of 1960 were in the process of being reduced down to 60,000 by 1970. The deliberate rundown of the South Wales coalfield in particular in an era of falling demand for UK coal, high quality coal in South Wales but difficult geology (especially for mechanised mining) and elderly Victorian/Edwardian sunk collieries. A community at Aberfan almost entirely dependent for their livelihoods upon the Merthyr Vale colliery, undoubtedly fearful (rightly or wrongly) that major expenditure on the Aberfan waste tip complex might have imperilled the very economic viability of this colliery itself in an era of mass pit closures across the coalfield.

The colliery itself did survive until 1989, and the final run down of deep mining 1985-94 in the South Wales valleys following the bitter 1984-85 national strike, for it had plentiful reserves and no politician was in a particular hurry to close it after the price paid for it by the community of Aberfan in October 1966.

What happened on 21 October 1966 should never have happened and should never be forgotten. It was itself a failure to learn from the past, a failure to inspect adequately and a failure to employ people competently trained for the tasks then allocated to them.

The result of a “system” that was not a system at all. The blind leading the blind, inheriting and continuing bad practices initially established to begin with by the blind.

Please observe, if you can, a minute’s silence at 9.15am on Friday morning.

No awards at the coal board for demanding site investigations. Dreadful outcome for those little children. A very good read.

LikeLike

It was Desmond Ackner QC who railed at the “callous , incompetence, ignorance, and inertia” that led to this avertible disaster. Half a century later, his conclusions have lost none of their power and relevance.

LikeLike

Pingback: Mid District Cup final – Bedlinog 22 Penallta 41 – the negative WRU pyramidal structural factors at play? – TheVietGwent